January 1980

[I live in Ashland, a college town in the hills of southern Oregon. I grew up here. It’s only been the past few years, for some of us, that we’ve begun to lock our doors.

I live alone, in a house I’m building, out of sight of the last streetlight, out where the nights are full of stars and moon. Marcella, my daughter, who is eleven, lives with me sometimes, sometimes with John, her father.

The other character in this story is Libre, a young woman of our local lesbian community. She’d once been my student; we had become good friends.

Note: I make no claim to have verified the truth of all that follows. This was the truth as we could learn it at the time.]

January 3

Just after Christmas, two eleven-year-old girls were murdered here. They left home in the afternoon, walking to the tennis courts. (I remember the day, with its welcome thin sunshine.) When the girls did not return, the parents called the police; the police said they’d certainly look, but that kids are often late. The parents began searching. Deanna’s father found Rachel’s body in the press box of a nearby football field. The papers said she had been strangled with “a torn piece of clothing.”

For another day there was no word of Deanna. We could only hope her dead. Then her body was found by some men out gun practicing on Dead Indian Road. She had been “suffocated” the papers said. Both had been “sexually molested.”

Suddenly I am shaking and my teeth are rattling. I never imagined I would write something like that in my journal. Writing it here makes it so much more real. I’m not even sure it’s right to risk reifying these horrors by writing them down. But then it already did happen. Here.

Of course we are all filled with horror, and grief, and anger, and fear for our children, our daughters, ourselves.

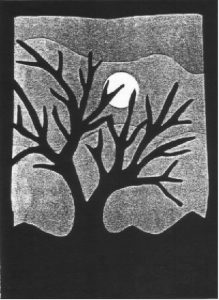

Libre had been keeping her sanity by taking long walks at night, being with the moon and stars, the wind in the bare branches. When I met her at the airport, back from a Christmas visit, driving her home, sitting and talking, I put off till the last minute telling her. Now at night there is mostly just the fear.

I’d hoped to do some writing this break; I needed to go for walks. But where I’s like to go, down dirt roads, on trails, I’m really afraid to go just now. . . .Though he may have left the country for all we know.

The town is full of mistrust. The older people are afraid of “the kids on drugs.” My radical women friends see in it the ultimate manifestation of the evil of the patriarchy. The women are afraid of the men. John relates a recent incident of a strange man being “too friendly.” Probably there’s no connection,” he says, “but you never know.” He says the word “homosexual” with an intonation appropriate to, say, “black widow spider.”

No one walks the streets; lines of cars await the children after school. It becomes apparent now, one reason we as a culture are so locked into using the automobile. Obviously, it’s a suit of armor, a motorized, several-thousand-dollar bit of protected space.

Libre can’t afford a car, has always lived without one. But she works as a breakfast cook, must be there by five. I’ve been loaning Deborah, when I can spare her.

* * *

Libre calls at seven; we plan a latihan. She’d like to walk up here, decides to chance it. There’s half an hour to wait. . .I build a fire, smoke a bit.

When she’s ten minutes late, I begin to worry; in twenty I call. She was just leaving.

Another half-hour.

Knowing I need help from somewhere, I think of the Tarot. I haven’t done it in a very long time.

I find the cards. I’d rather imagined

shuffling them once,

so I do. Cut, so.

Now, fan them out.

And center.

What am I asking?

I must ask what’s on my mind.

The words I find are:

“Who is the rapist?”

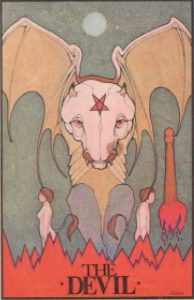

One card is obviously it.

I take it, turn it so:

THE DEVIL.

A dread face, animal skull,

human eyes, red in the melting flesh,

weary with evil.

Fangs, wings fill the sky.

Below, flames,

billows of smoke, little naked people,

a woman on the left, on the right, a man

moving away from each other.

. . .Yet above the wings, above the forehead,

scarred with its red, inverted star,

above them obscured by smoke,

but still there, over all,

the moon and stars,

abiding.

But the image is so evil! (Too, the devil’s face is very like the face of a student last year who really did often frighten me.)

I have to ask, “Please, give me a little perspective on this,” and accept the next blue cars; it is “Death.” Another skull face, yes, and scary. But I have seen the death card once before, when Grandma died. And I know that it also means the vast change that is death, the reminder of what lies beyond.

Still, it seems grim, if exalted. Is there no worldly hope, or advice? Is there anything I should do by way of protection?” “The eight of cups,” it answers: A bowed and grieving figure. Liquid shadows. Mountains, and the moon. Her long cloak merges with the earth itself. The moon is very old, almost new. Desolation. Aloneness. Sally Gearhart calls this card “continuation”: moving forward through disillusion into oneself. “That point in the journey into the self when we know the process to be irrevocable. There is nowhere to go, but on, no one to accompany us but the moon.” Another book speaks of the coming daylight, and a dawning understanding that banishes fear.

That’s all I can ask. In a few minutes Libre is here. We talk a bit; do I read the papers? Do I want to know more? I don’t. And I do. At the restaurant where she works, she says people talk of little else. The police aren’t releasing details, to spare the families, and because they need their secrets, but it seems a bloody quilt may be an important clue. There was a picture of it on the front page today, in case someone should recognize it. “It was an old, handmade quilt,” she says.

She has found her gun, and carried it with her tonight up the hill. Unloaded. (She’s not even sure even that is legal; she’s still too young for a permit.) It felt safer, she said, feeling its weight in her hand as she came up the last, deserted part of the road.

I’ve never held a gun. She opens the chamber and hands it to me, explaining how it works, and how it’s cared for.

She has felt ambivalent about the gun ever since she’s had it. Usually it’s been packed away, unloaded. Last night, though, she dreamed that her sister was being raped. Her mother was sobbing, “Somebody, do something!”; and Libre was crying, “If we only had a gun!”

We place it on the altar, with the candle and the cards. We find we can also speak of other things. And the fire is beautiful. We settle into quiet before latihan.

Latihan is everything. Anger and fear, grief and horror. But for me it is also full of singing, in a voice that is sure, and very, very strong.

Afterwards, I show Libre the safer way home, over the pasture. The moon is wonderful, one night past full. The grasses are tall and stiff and grey, there are clouds and stars. The wind is soft, warm, bracing. The night and safety invite. “Lets run around,” I say. We run, uphill and downhill, giant steps, the gait of power. We leap. We sit. We move as we wish. Each with herself and with the night, each making safety for the other.

We hug good night.

“Walk safely,” I say.

“I think I will, now. Good dreams.”

“Blessed be.”

I walk slowly home. The lands around, the bushes, and the road, are empty, peaceful, and full of moonlight.

Monday, January 7

Yet she went home that night to sleep not more than a few feet from him. Friday evening the police descended on the duplex next door. The man had left the night before. They are calling the house “the alleged crime scene.”

They are saying she was alive most of the time.

Libre’s been staying here nights since then. Cars drive constantly past the place there; strange people come around. She can’t let fear itself drive her from her home. But yet — in the past month she’d once or twice thought she’d heard someone at the back window. We’d talked about it; she didn’t want to be paranoid. Then, that first day when the police came, they found his footprints there.

We hear it on the radio the next day. They arrested a man, Manuel Cortez. “Wouldn’t you know it,” an older woman exclaims. “Those Mexicans! It seems like they’re always doing something violent!”

A Mexican-American woman has called a news conference. She asks that we not hold hard feelings against them all, who are as shocked and grieved as we are.

Wednesday January 9

Ethics class began yesterday. I thought I was well-prepared; but I found myself disconnected, trying to say and do too much at once. Some of it came out sounding negative and defensive. . . .Partly, it’s always hard just at the beginning when we don’t know each other yet. Partly, I am unfamiliar with the “teacher role” after a month away. And then there is the large proportion of “hulks” in this class, young men I know or guess to be silent onlookers. (From here, it looks like contempt; and some of it is, and some of it is fear, and other things.) Hulks, anyway, whom I despair to rouse with poesy.

If we are to do what’s most worthwhile in here getting to know each other and ourselves, speaking what we know of right and wrong, we will have to find a place of trust. But here now in a minute we will talk of rape and murder, here and now. And when we do, we cannot find the trust.

Some students from Los Angeles say, “The reason you’re taking it so hard here is that this is a little town. ‘Happy Valley.’ In the cities we’re really more used to this sort of thing.” Many feel, “This was one sick person. What we need now is to forget it and get back to normal.” One young man exclaims earnestly, “He just shouldn’t a’ raped ‘em and killed ’em too. He could a’ either just raped ‘em or just killed ‘em; but both together, man, that’s really terrible!”

The women speak of anew fear of walking alone at night. And the mane, too, say it’s hard, to be met with such fear and suspicion. We talk about self-defense for women. I raise the question of being armed in some way. I can feel that this disturbs them. I talk about my own solution for this time, carrying tear gas. I’ve brought it with me, thinking I might hand it round so the women can see and touch it. But the class mood is suddenly making me fear there just might be a rule against professors bringing weapons on campus.

I speak of my own process: “I’ve felt safer in some ways having it with me. And yet, the thought that this object is in my hand in case there’s a murderer in the shadow behind the next bush is not really reassuring.” Vigorous nods agree impatiently with that.

I finish by reading to them from Susan Griffin on the need for solitude and the fear of rape. I can feel some women are touched by it. In parting I say, Imagine. . .Imagine a poet musing in the twilight above an abbey. Imagine, then, a policeman handing her a card: ‘If I were a rapist, you’d be in trouble.’

The afternoon class was bigger, warmer, and more open. There were more older people, and more women. Parents. And people with relatives in the sherriff’s office. We asked our questions, pooled our information, shared our lives and feelings of the past few days. “This was exactly what we needed.” they said. “None of our other classes mentioned it at all.

* *

I felt so encouraged by what had happened in the afternoon class that I decided to try to take some of it back to the morning group. So I composed the following progressively-less-linear-set of lecture notes:

- Capital punishment. Have the murders changed or reaffirmed your views.? (Jeri said that the man who killed the little girl in Medford four years ago is already on an honor farm; he may soon be back among us.)

- The media. As you see it, is there a connection between movies and books filled with sex-and-violence and actual crimes of this kind. (Most students said they didn’t doubt it..)

- How do you feel about police advice to women not to walk alone at night? (The police have returned often to the house. Needing to know, Libre asked one of them, “Do you think it’s safe now? Can I walk at night again?” The policeman would not say. But his advice for any time was that if she wants to go walking at night, she should go with her boyfriend.)

- How do you react to the real possibility of this in your life?

- Question: If you believe that God is good, or that at the heart of the Universe there is basically Love, or some such, . . .well, how?

- The parents. The support they’ve had. I’ve heard they’ve opened their homes to anyone who feels moved to come to them. Often they share photographs, stories of their daughters lives. sometimes they are the ones to do the comforting.

- Our need to know the facts. Is it safe now? Was there just one man? Is this the man? whose car did he use? Many of us don’t see how one man could have done it. We cannot get the information we need to judge our degree of danger till the trial, months hence.

. . .Well, how could one man capture and quiet two little girls with tennis rackets? Catch one, and threaten to kill her if her friend screams? . . .One wonders, did they think, those little girls that death was the worst that could happen? Yet what do we tell the children now? The police say to the school assemblies that the girls were “killed.”

Can I, ought I, say to my daughter the things I have heard now? Should I even say them to you? That the child found first had been burned with a blowtorch. That the one who lived all that day and another night was found so cut up that they couldn’t tell for a while whether she was a girl or a boy. Even then I have not said all.

“I can’t help but think sometimes,” Jeri said yesterday, “how Deanna’s father must have felt, finding her friend’s body, and knowing that his child was in that man’s hands, and no way in hell he could get to her.”

. . .Washing the dishes this morning, a jar breaks in my hand, slicing off a chip of skin. Hot water on the cut is sharp, burning; but even as I “ouch” and shake my hand it subsides. . . .I cannot imagine that pain multiplied by what was done to them, times the hours it lasted.

. . .I think of Joan of Arc as Ingrid Bergman, triumphant in the flames.

. . .I hear Libre saying, “I know there is a way to handle physical pain. Being an abused child, I had to learn how to handle it.

. . .I remember in Eugene a woman student telling us how once pain, and once, oh, Goddess, yes, I remember now, once fear, sent her “out of body.” She was across the yard, or down the trail, looking back at herself.

. . .I think of the words of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross to a Medford audience when there had been a four-year-old killed there. “the parents of this little girl must know,” she said, “that this experience was not for her as you think. From all our studies I can tell you, and for their own peace of mind they must know, that this little one left her body very early on. From then on she was not frightened, and she was not alone. She was with someone she loved and trusted. She was probably aware in some fashion of what was happening to her body. But she no longer was that body; it was not happening to her.” . . .Maybe Kubler-Ross is right. Maybe she does know. That had better be how it is, if there is to be any hope of a meaning to it all.

. . .And if there is a meaning to it all, and lessons to be learned here, I’d best be looking for them. . .Words, I remember, often offer clues.

“The Press Box.”

Yes, exactly.

“The Media Cunt.”

is another translation.

And the other, left on “Dead Indian Road.”

Those syllables have rolled from our lips

for generations here unnoticed.

“Dead Indian,” a name and nothing more.

And now another name, “Cortez.”

A son of raped and dying Indians

wearing an old and evil name.

The news announcing his arrest

brings fresh horror, a four-year-old

in Portland. They say the killer this

time was a girl-child of thirteen.

* *

The phone rings. John. Has Marcella called yet? She was supposed to phone when they reached her friend’s house after school. The number’s been changed; it’s unlisted. John sets out to locate them.

. . .I think of their most likely path, along a dirt alley past a parking lot, then through a little wooded place near a ditch. We’d talked at length about whether it was safe enough. She’d said there would be many kids walking together. And, after all, we have to stop being so afraid sometime . . .we’d said.

Thirty minutes passes. The phone rings. My voice will not stay steady as I answer, and a small voice says, “Hi, Mommy. I just remembered.”

Saturday, January 19

I feel I should leave lots of blank pages for the days I didn’t write. I ended up reading from those “lecture notes” to the morning class, with such negative results I haven’t written anything since.

. . .I suppose I really should have known better. I wouldn’t have inflicted those thoughts on Libre, or anyone else in my life right now. And since Sunday when I finally got a little solitude and time to heal, I haven’t wanted to think about it either. A certain amount of going on to other realities is necessary.

. . .If they’d been a class roomful of Annie Dillard fans it would have been different too.

I knew I was taking a risk, saying these things. But I went ahead because I also knew that I would feel more afraid than I could bear if I must know these things, but could not dare to say them.

. . .I try to meet my classes in as centered and open a state as possible. I often feel their unspoken thoughts and feelings. Reading them what I’d written, I felt it, tangible as a wall, that they did not want me to say what had happened to the girls. I muffled it in general words; “torture,” I said, “mutilation.” Only.

. . .Sometimes, too, I felt real hearing happen as I read.

Then I passed the apple in the circle:

Jeannie said, “When something like this happens, you know, sometimes I wish I hadn’t been born a girl. The rest of the time I love it; but in times like this, I do, I wish I didn’t have to be a woman.”

Her fiancé, next, a criminology major, said, “I feel that reading this kind of thing is not at all helpful. You just can’t dwell on it like that.” As for police releasing information, he patiently explained about prior media coverage and fair trails. The words “dwell on it” are repeated by others.

. . .I wonder if a hypothetical intimate would have noticed it then, how Deborah Kerr took over. She sat there on the table in my body in its long skirt, and nodded and listened sympathetically to all the things the different students had to say, while I crouched somewhere deep inside, cowering in the focus of so many feelings, so much anger.

“I knew Deanna!” Kelly said. “I don’t want to think of her that way! I want to remember her when she was alive!”

Julie recalled, “The night after I first heard about it, I was just doin’ the dishes when I started to cry. My little brother came and asked why I was cryin’. I didn’t know. So her asked me, ‘Sis, is it because of what happened to those little girls up in Ashland?’ And I realized that, yeah, that was it, that was why I was cryin’.”

“This is exactly why I’ve always insisted on knowing exactly where my daughters were at all times.” That’s Clyde, Air Force, retired. “Sometimes they got pretty mad at me, but I did it anyway, and I’m glad now that I did.

Sue drummed red fingernails on the desk. “In Portland, I didn’t tell my folks where I was going. My girlfriend and I, we’d say we were at each other’s houses, then we’d go to a dance over in a part of town where some of those murders had been happening. . . .But you can’t just stop living. I hope this is the last day we talk about this stuff.”

Many stuck to the earlier discussion of capital punishment. One man recited the three cases for which there should be capital punishment. To my surprise, one of them was “being a revolutionary.” “Because if you just sentence him to life in prison, he’ll think all he needs to do is wait till his friends win the revolution, and they’ll let him out again.”

After class, Don, a student friend, came by to share some writing he’s done on his time in Vietnam. The talk turned to horror movies. Will the local theater go ahead with If A Stranger Calls? (Plot: teenaged babysitter is terrorized over the phone. For years. Finally he does come for her.) I spoke angrily of the images that confront us even in the grocery store, the woman on the magazine cover, helpless in the doorway, the bloody axe descending.

Don had to admit he likes going to horror movies usually. There was one, though, a few weeks ago at the drive-in. . .A woman is lured to a certain house, then strapped down, tortured, and disemboweled. The plot consists of a series of such murders.

* *

The afternoon class proved healing. I was much too afraid to try reading from my notes again, but we shared some deep feelings.

After class, a small group stayed talking. A woman said, “You know, something I heard that helped me: There are two sixth-grade girls, one was a friend of Deanna’s, the other of Rachel’s. Each of them had a dream in which her friend came to her saying, ‘We’re all right now. But, tell me, how are our parents?’”

The day left me shaken. Coming home, I found an envelope from Carol: a small blue bow, an old metal keyhole, a white feather, a bit of rock, and a lovely green bud. I take these gifts to mean: Remember to play. Be sensible, lock your doors. Remember to write. And the beauty of nature. And look to the sources of healing.I wear these charms about me now, or keep them on my altar.

Marcella was here for the night, and Libre, who was sick, hibernating in the back room, listening to the rain. It felt good; we three somehow fit together smoothly,and having them both here felt so safe.

The next day I went to Esther’s for a massage. I could hardly bear to be touched; it was so hard to trust any touching again. I began to cry. She stopped and we just talked for awhile. She shared her own process around the murders. She saw, too, how vulnerable I must feel. It helped a lot. The she covered me and rocked me gently, and let me cry some more.

At latihan Sunday with the Subud woman, the whole time I knelt and cried. Neither time did the tears feel over. Never yet the transition to something glad or comforting. And yet it healed me.

That night, alone again for the first time in awhile, I began to clean the house, and even started a jar of sprouts. Best of all, I found that box of writing I was afraid was lost. I was not surprised to notice that healing came just now, when the moon is very old, almost new.

* * *

Sunday, January 20

Last night, Marcella and I finished reading The Far Side of Evil, by Sylvia Louise Engdahl, which was, in a way, too close to the topic, involving, as it did, images of torture, and grim dictatorship. but the heroine, Elana, knows a way of dealing with pain: not blocking the pain, but instead finding the part of herself that feels the pain, as it were, but doesn’t suffer from it.

Well, it’s worth trying, if you should need it. . . .It’s also really a kind of metaphor for what I try to do day to day. I wish myself better success inextremis than I’m having right now.

When we woke up this morning, Marcella told me a dream:

“Well, I was several different people in the dream, and yet they were all me. . .

“First I was just me, a few years older than I am now. I’d gotten married, but life went on just as before; he went on living with his parents, and I lived in an apartment with mine. You see, we weren’t really much older than we are now.

“The guy I was married to, he’s a kid in my class, Casey. I don’t know why; I don’t ‘like’ him or anything.

But now there comes a different part. In this story we were in an airplane; there were about six of us, and we were stewardesses. And this Dracula thing was killing us, one by one. . . .Only it was really all a sort of game I was playing with Kirstin. . . .When he came to me, it was so scary that I decided I’d just step out of the story, like, so it would be as if that stewardess had never existed. . . .But then I thought , ‘Oh, what the heck, I’ll get killed.’ So I stepped back into the game. Because I knew it wasn’t really so bad. It’s the part before you get killed that’s so scary. It was actually very quick to die.

“. . .Then I was back in the main story again. We were all in this big supermarket, the biggest store I’ve ever seen. The rows of stuff to buy were like a maze; you could get lost in there. And it was scary because that Vampire thing was in there. We were all pushing grocery carts around, not to buy things, but still we had them. I guess they might have been some protection; you could shove one at him and keep him away, maybe, but you couldn’t pick it up and hit him over the head or anything, of course.

“I didn’t know where Casey was. He was somewhere in the maze, though. Just about everybody was. (I don’t know why we didn’t all run outside; but I guess there weren’t any doors. I don’t know how we got in there.)“

Anyway, I was with a friend, one of the sixth-grade girls. Who? Well, it was Rhonda. Or, Sherri, or I don’t know, it was sort of like all of them in one, if that makes any sense. The first time we went through the maze, it was very big and scary. But the second time around it was easier. Just as we were turning into it for the third time, I sort of saw. . .something. . .out of the corner of my eye. I didn’t really pay any attention to it and neither did anyone else.

“What it was, was there were two kids up there on an inner balcony, like a fire escape, but on the inside. And they couldn’t get down because that Vampire was barring their way. We were halfway round the maze again when I suddenly realized what I’d seen. ‘My God! And that was Casey up there!’ We raced back. . . .And now comes the part where I was Elana, like; because I did the only thing I could do. They were absolutely trapped anyway. So I did something to get it over sooner. I reached up and pushed a button that made the floor flip up, and it just sort of catapulted them towards the Thing. . . .And when that happened, they just. . .relaxed. You’d think they’d be even scareder, but instead, as they were flying toward him, they just sort of let go and. . .relaxed. (I was surprised when I acted like Elana that way.)

“Then at the end comes the part where I was Laura. Yes, Laura Ingalls Wilder. I was in a little room off to the side; there was this long hall, and off of it were little rooms where you could just go and be, and think, or write.

And I was Laura, sitting at a table,

writing about my life. For some reason,

I was much older, though that Vampire

thing had just ended. They’d finally

caught him, I guess.

“Still I was a lot older. . . .Feeling kind of

sad, and kind of peaceful. . . .And I was

just . . .writing about my life. . . .

And that was the end

of my dream.”