Ruth Mountaingrove turned 60 this year. She’s been celebrating all year, giving herself permission to get it some artistic projects long simmering: assembling books of her photographs, recording her third collection of songs.

But she also wanted to set aside a special day to celebrate with her community. “60 is the point at which a woman is considered by the patriarchy to be a sort of zero, nearly useless. So I wanted to explore what turning 60 can mean when one is part of a women’s culture.”

She asked the women of Fly Away Home to create a form for the celebration. It was not to be a “birthday party” as such–her Pisces Natal day came in the muddy months . But also, Ruth had something different in mind for the event.

Mid-morning the women were there. Ruth was the oldest; but there were women from each earlier decade of life, down to Ruth’s Goddess daughter, Miranda .

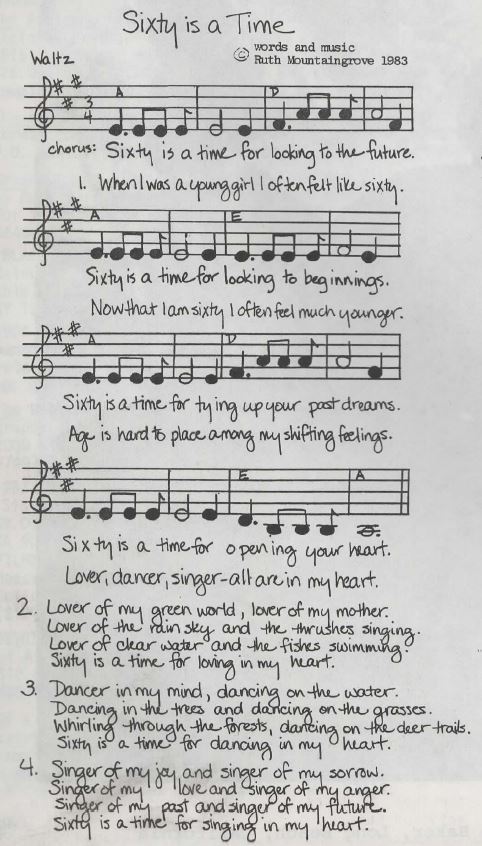

The circle began with a song which became a sort of mantra for the day; one of those simple, lyrical waltzes that dance from Ruth’s heart from time to time.

Then Hawk led a guided meditation: “Make yourself as comfortable as you possibly can.” Laughter from the 30 women perched in the grass on the sloping hillside. Her voice centers us in, to our bodies, to the earth supporting us, to the rush of air in our lungs and nostrils as we become “simple, breathing body.” And deep within that body we each begin a journey– from the sunlit meadow to a path in the forest where pupils dilate and senses quicken, towards a waterfall. “You know who it is even before you see her. The look of her, the feel of who she is comes so clearly to you. You know it is Ruth, there beside the waterfall.”

My Ruth sits on a rock playing her guitar and singing, wordlessly. There is only the haunting melody, but it has to be… “My Love is Like a Waterfall.” So it is!

My Ruth never holds still for long, though, comes in multiple exposures. Sometimes she wears her usual country plaids and jeans, sometimes nothing at all, or a witchly garment. Sometimes her hair is dykeyshort, as of recently, sometimes down past her shoulders as it was when I first met her at 53, sometimes very long, streaking grey patterns down her robes as she bends to her harp, I mean, guitar.

She notices me, asks me a question. “How are you?” Hawk’s voice tells me to hold the question in my heart. Oh, dear, it was supposed to be a cosmic question. But then, with Ruth, it just could be.

“Now go to Ruth and spend some time doing whatever it is you most enjoy doing together.” But we never can decide between Ruth singing and me being her groupie; or her taking pictures of me; or me reading my writing to her and Jean, and them being the first to tell me that it matters; or just enjoying the whole world they hold up there at Rootworks. (Once, years ago, I wrote to them from a parking lot out in the patriarchy, “Being able to write to WomanSpirit is like being able to send a letter to Oz.”)

Near the end of our time together, she gives me a gift, a sepia photograph, which materializes in her hands. Another wonderful portrait of me, I expect. But, no, it is a portrait of herself, singing, and smiling as only Ruth can smile, at 60.

Then it’s time to go. She turns, pulled back to her waterfall, and I realize that in the cave behind the watery curtain, she has… of course! Her darkroom.

… Returning then back along the path “to the meadow where you sit in a circle of women, women who have each walked their own path to meet Ruth.”

“And let there now emerge one word to describe the person you met by the waterfall.”

We began making music with the words, lofting a bubble of sound around us made of words like playful, and gentle, friend, muse, an iridescent dome built of musical, sister, illumination, the muse of swords, warm and strong and playful.

Bonnie then began a circle, introducing ourselves by way of some connection we have with Ruth, picking some glimpse to share, some story of her in our lives.

She remembers their first meeting, three years ago; the dark little lane through the woods, the cabin, the undeniably witchy feel. “Jean was in bed, asking me all who I was and you were tending the fire … ”

” … And I especially remember when Fly Away Home put on our play* how you came up afterwards and you said ‘You’ve got a tiger by the tail!’ That was exactly how I felt, and I felt so glad that you saw it too, and were acknowledging us.”

“…And I love it that you’re so brave as to do without your front teeth. I have soft teeth, and my day will come, and to me you’re this ‘bold model of toothlessness.'”

Then Pan (Pan Tangible, Miranda’s mother): “Well, the first I knew of Ruth was when she and my mother fell in love.”

Jean’s funny story. On and on, down the circle, the meetings over all the years, the things appreciated and remembered. Ruth picking huckleberries, Ruth, known for three days or ten years, known through songs held to hearts on busses, or in the forest sawing wood. “Yes, oh, yes, this way is good.”

“…At the waterfall, you gently, but with challenge in your being, asked me, ‘What are you writing now, Bethroot?’ It held my sense of you as someone who is not only indefatigable in your own doing, but in your confidence that I also can, and will, and should; and that the rest of us can, and will and should … ”

Ruth photographing a lover’s quarrel, “It was an interesting way to have a fight,” mediating another disagreement, each story from another angle, each story conjuring up another person who is unmistakably Ruth, until she stands sculpted roundly before us, in the circle of her friends.

“It would take a strong woman to bear it,” I thought at the time. “I don’t remember ever being able to stand that much attention before,” she told me later, but this time it was easy. I found that I liked it.” We sang: “ Ru u uth you are beautiful, Ru u uth you are strong, wonderful to be with, carry us along, Ru u uth hear our loving song.”

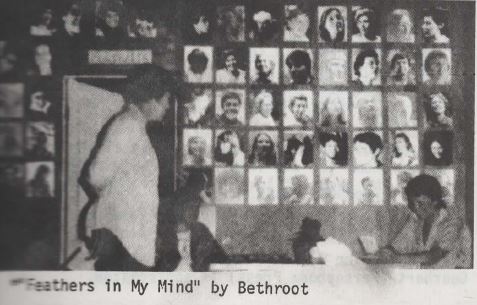

Bethroot reminded us of Lammas near, and of harvests present and to come, and of the harvest of Ruth’s photographs displayed in Natalie Barn across the way. And so we turned to lunch, a feast of shared food around a big table under the trees.

After lunch I spent time in the barn with Ruth’s photographs. The room was, to me, a celebration of women. There was a wall of portraits, clusters on women “working,” “relating,” “gathering,” “making music.”

I stayed long before the collection of faces, absorbed by the varieties of woman-strength I found there, feeling the richness of the friendships in her life.

Among “relationships” I found a couple who were once my friends, long since gone their separate ways, but here, forever, still smiling affirmation to each other. “Yes,” says the picture. “It was real. I saw it, too.”

Then suddenly women were pouring into the barn, hands joined in a snaking spiral, calling out, singing: “Ruth is remembering … Ruth is remembering… Join in the spiral … ” The line lengthened and threaded its way to the meadow where we circled. “Ruth is remembering … remembering … remembering … ” like the ripples of a bell dropped into silence under the trees. “Join in the spiral… ” With each turning we drew slowly in until finally we whorled closely around. Then Ruth was seated on a comfortable pile of cushions; and we settled down to listen.

Then suddenly women were pouring into the barn, hands joined in a snaking spiral, calling out, singing: “Ruth is remembering … Ruth is remembering… Join in the spiral … ” The line lengthened and threaded its way to the meadow where we circled. “Ruth is remembering … remembering … remembering … ” like the ripples of a bell dropped into silence under the trees. “Join in the spiral… ” With each turning we drew slowly in until finally we whorled closely around. Then Ruth was seated on a comfortable pile of cushions; and we settled down to listen.

Bethroot’s voice began to read: “The woman who was to do the remembering was enveloped by them in a great spiral. Surrounded by everyone, she relaxed into deep memory. Her stories and reflections flowed out. And her listeners were so attuned with her that they relived her experiences. They felt her feelings, thought her thoughts, knew her knowings. They participated with her, a chorus of voices shimmering with the power of one woman’s lifetime.” And then softly, “Are you ready, Ruth, to do a remembering? And may we ask you questions? And may we be sounds for you?”

And so for an hour and more Ruth looked out past the treetops, to miles away and years ago, and told us what she saw:

Philadelphia, the end of the sixties, a women’s center in an old Victorian house. The birth there of “Women in Transition,” and of a women’s newspaper named Awake and Move. “Awake and move, “a rippling chant whispers through the circle. “There were only women there, so we had to rely on ourselves. And what we learned from that was that women can do anything… There was such sisterhood, such acceptance of you whoever you were.”

Further back, earlier stirrings of feminist understandings. The precious few early feminist books and publications, encountering sexism in her work situation.

The birth of a daughter. “That’s when I got a divorce. I’d always wanted a daughter, and she was lovely; and that’s all I was going to do of a marriage… Recently a woman came through here with a new word I’ve needed. She caller her ‘ex’ her ‘wusband.’”

…A glimpse of Ruth and her young wusband moving into a tiny row-house, wondering if the bathroom will arrive before the baby does; and a Titwillow-esque song on the occasion: “You promised us plumbing a long time ago. We’re waiting… we’re waiting… we’re waiting…” …”And while we were still in that little house I gave birth to three sons.”

Back further, a first-born, a son, too, dying of pneumonia in a crowded hospital at three days old. A deep depression. Solace in a kitten and in writing.

…Growing up in the thirties. “My mother, who was a very shy person, went from door to door selling Pitkins Products, toothpaste, spices, hand lotion. My father would drive her around, and she’d go up and knock on the door… It was her work that kept the family together.”

…Growing up in the thirties. “My mother, who was a very shy person, went from door to door selling Pitkins Products, toothpaste, spices, hand lotion. My father would drive her around, and she’d go up and knock on the door… It was her work that kept the family together.”

“One of the ways we got through the Depression was, I remember when I was 11, going up into the forest with my father gathering wood. We’d bring it home and saw it up together.”

“Two women, two women, on a two-woman saw,” sing the women, seeing where this story leads.

…And improbable inventor uncle with a wooden leg. College on a shoestring. A glimpse of Ruth as a young science teacher in 1945 explaining what an atom is to the school board, who suddenly wanted to know.

“When did you start to write?” Were you writing in those years?”

Poetry at seventeen. Her book For Those Who Cannot Sleep written while mothering three sons, tending to both her family’s needs and her creative self, but at a cost, a breakdown.

The search for companions. The artists at New Hope, the “Newcomers’ Club” in Jenkintown; “You introduced yourself by saying what your husband did.” The Quakers, a poets’ group, “single parents,” a workshop on communes, and there in a corner sits Jean.

… And the long road yet that sends Ruth across the country after her in a motley caravan of women and kids. “In Detroit we met a woman who had ‘just driven off’ with the family VW, her two boys, and her gas credit card. So she joined us … ” Repairing their own cars, tending the kids, they finally made it West. Ruth made it to Jean on a commune in Oregon; and we left them there, at the beginning of their life together, giggling into the night, and the kids calling up “Go to sleep!”

… Surfacing in the meadow with that same person now, as she celebrates 60. We thank her for her stories, for her life. We stir, we stretch, and become again characters in “The Further Adventures … ”

After our stillness, activity is in order. We gather into small groups for making “gifts.” Meanwhile, there are massages for Ruth and Jean in the dappled shade up by the garden, as Miranda wiggles on the blanket near.

For the “presents” we re-gather on the grass. There is a gift of “dance and movement”–a long green tunnel of a dragon, exploding into sounds and costumed dancers. A gift of words, a collective poem. An impromptu song in honor of Ruth. And a giant “birthday card.”

For the “presents” we re-gather on the grass. There is a gift of “dance and movement”–a long green tunnel of a dragon, exploding into sounds and costumed dancers. A gift of words, a collective poem. An impromptu song in honor of Ruth. And a giant “birthday card.”

We end with the singing of her song. “Dance with me,” she says, and women spill into the meadow, waltzing and singing of sixty. Ruth is passed ’round the circle for kisses and hugs, and the day is over .

It left me so proud of us all, so grateful to have friends like these. In the end, for me, the day was not so much about Ruth, or being sixty … Or rather, precisely because it was so powerfully about these things, it became an exploration of the nature of celebration itself.

I’m grateful for Ruth’s present to us all, and to Fly Away Home for the inspired way they made it be, and for the looks of love that day on all the women’s faces.